For the last few months I’ve been working on a few Elixir applications receiving inputs from different sources: queuing systems, websockets, database notifications. In this post, we’ll look at one possible way to model the architecture of such an application.

Requirements

Our application needs to:

- process messages whose shape can change over time, but affect the system in the same way. In other words, it has to support different versions of the same client at the same time.

- Provide traceability for an incoming message, so that it can followed through at all stages.

- notify different clients of certain events after processing the message.

As an example, here’s a more concrete use case:

- The application receives an incoming RabbitMQ message: create a report with this data.

- The application processes the message and creates the resource in the database.

- Finally, it sends a few different notifications to another message broker (Crossbar) so that they can piped to any consumer client (browser, mobile, etc.)

- At every stage, log accordingly, using a

request_idparameter included with the first message to trace the flow all the way through.

Approach

We’ll heavily leverage polymorphism.

We can structure the application logic by:

- Defining a protocol for each step: message decoding, persistence, logging, notification.

- Define as many versioned structs as we need along each step.

- Implement each protocol for each struct.

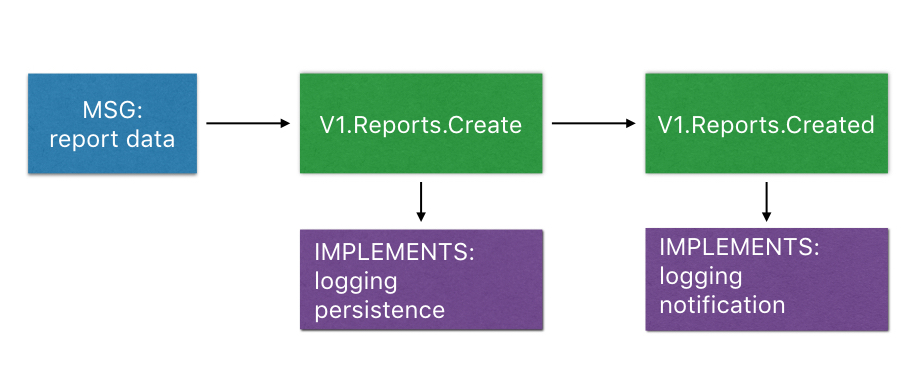

If we apply these ideas, the whole flow can be represented as follows:

In practice:

- as a message comes in, we proceed to identify it and package it as

V1.Reports.Create - We implement the logging and persistence logic for that specific struct

- After persistence, we return a

V1.Reports.Createdstruct - Again, we implement logging a notification for that specific struct

This design allows us to:

- split the problem into clear areas of responsibility

- have explicit guarantees each step of the way: every struct has a predictable set of attributes

- Unit/property test every step very easily

- Extend the application by adding more structs, therefore increasing size but maintaining the same level of complexity

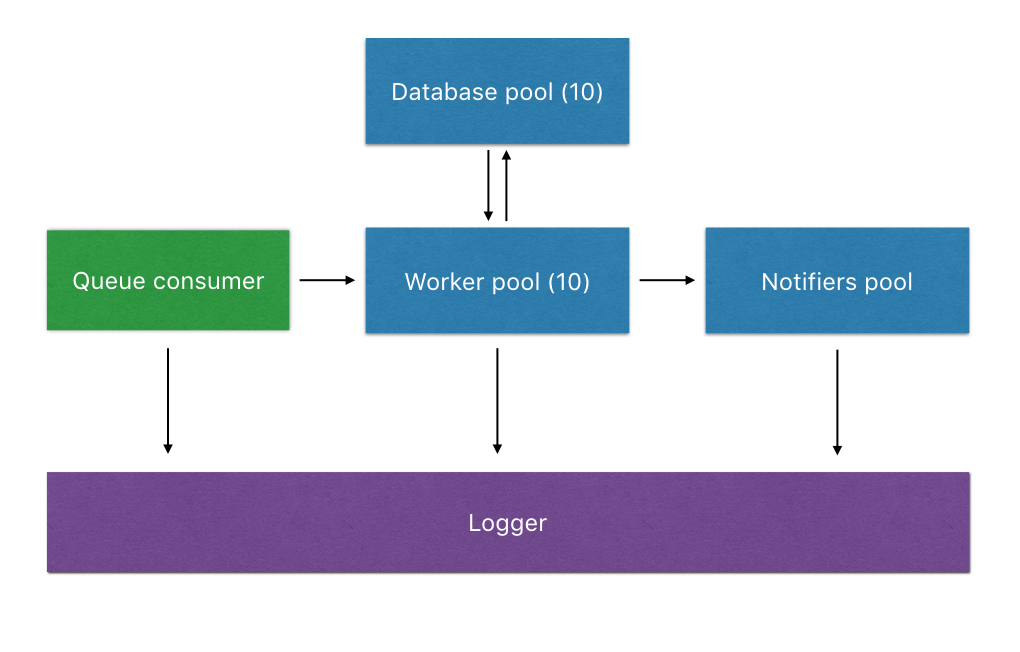

In terms of processes layout, here’s how it can look like:

- We have one consumer to process and identify an incoming message;

- The resulting struct is passed to a worker (checked out from a pool). Using a pool allows us not to outperform our database capacity. In this scenario, we have one worker per database connection;

- After that, we pass the result struct to a notifier pool, which will publish the relevant messages to the other broker;

- All along the way, we interact with the

Loggermodule.

This setup mirrors the division of responsibilities we outlined in our protocols, to the point that it naturally leads to reusability across different applications.

Code implementation

As it’s upractical to show the entire application in a blog post, we’ll focus on some key areas.

General flow

It doesn’t really matter which queuing system we’re using, we just care about a few key properties in the incoming message:

- explicit version

- a request id that we can forward to the rest of the chain

- a clear directive/topic on what the message is about

For instance, our message could look like this (using JSON as notation):

{

"meta" : {

"version" : 1,

"topic" : "reports",

"type" : "create",

"request_id" : "15456d4e-782b-11e5-8bcf-feff819cdc9f"

},

"data" : {

"reference" : "ABC7193",

"description" : "He's walking in space!",

"submitted_at" : "2015-10-27T09:23:24Z"

}

}

The format may change (e.g. the topic could be inferred by the queue name itself), but generally speaking this is a good baseline.

In our consumer logic, we want to aim for something along these lines:

message

|> identify

|> populate(message)

|> log

|> process

|> log

|> acknowledge(client)

|> notify

|> log

We can chain all operations and produce a very readable pipeline. We’ll come back to this structure later on when we talk about error handling.

Identifying the message

Thanks to the metadata included in the message, this is relatively easy.

Let’s first define a V1.Reports.Create struct.

defmodule V1.Reports.Create do

defstruct request_id: nil, data: %{}

end

Version and topic are expressed by the struct name itself, so we don’t need to store them. We add a request_id attribute so that we can keep track of the request flow and a data attribute to store our domain specific data. Note that depending on how strict we want to be we can also opt for something like:

defmodule V1.Reports.Create do

defstruct request_id: nil,

reference: nil,

description: nil,

submitted_at: nil

end

In our case, we’re gonna stick with data as we need to be more flexible (our reports may have some additional fields and our database can handle documents with different shapes).

To identify the incoming payload, we can write a function like:

def identify(payload) do

case payload.meta do

%{"version" => 1, "topic" => "reports", "type" => "create"} -> V1.Reports.Create

_other -> {:error, :unsupported_payload}

end

end

We aggressively pattern match to quickly determine the struct to use; this approach scales really well even with a dozen different combinations. Beyond that, we can use metaprogramming to infer the pattern match clause from the list of payload structs available in our codebase (this is left as an exercise to the reader).

Populating the struct

To populate the struct, we can define a populate/2 method:

def populate(struct_module, payload) do

%{"data" => payload["data"],

"request_id" => payload["meta"]["request_id"]}

|> Enum.into(Kernel.struct(struct_module, %{})

end

Using Enum.into/2 assumes that our struct implements the Collectable protocol. As explained in the official docs, we can think about this protocol as the counterpart of Enumerable: where Enumerable defines how to iterate over a certain data structure, Collectable expresses how an iterable data structure can be piped into another.

This means that we need to define the Collectable implementation for V1.Reports.Create:

defimpl Collectable, for: V1.Reports.Create do

def into(original) do

{original, fn

s, {:cont, {k, v}} -> update_struct(s, k, v)

s, :done -> s

_, :halt -> :ok

end}

end

defp update_struct(s, k, v) when is_string(k) do

update_struct(s, String.to_existing_atom(k), v)

end

defp update_struct(s, k, v) do

Map.put(s, k, v)

end

end

Our implementation happily accepts a map with either string or atom keys, safely using String.to_existing_atom/1 to handle the conversion .

With this code in place, we can expect to have the following struct as a result:

%V1.Reports.Create{

request_id: "15456d4e-782b-11e5-8bcf-feff819cdc9f",

data: %{

"reference" => "ABC7193",

"description" => "He's walking in space!",

"submitted_at" => "2015-10-27T09:23:24Z"

}

}

Logging (part 1)

To log, we’re gonna leverage the standard Logger library provided by Elixir. The log/1 function we added to our pipeline can be as minimal as:

def log(item) do

:ok = Logger.info item

item

end

We return the item itself not to break the pipeline.

In order for this to work, we have to implement another protocol, String.Chars, which defines how a given type gets converted to a binary. Let’s do that for V1.Reports.Create:

defimpl String.Chars, for: V1.Reports.Create do

def to_string(create_struct) do

"type=create status=accepted request_id=#{create_struct.request_id} reference={create_struct.reference}"

end

end

It’s important here to decide what matters in terms of tracing a payload through our system: while the request_id is a given, we can be flexible about other data depending on security/privacy concerns.

We’ll just log the reference, which will allow us to tie this specific logging event with subsequent persistence events. The use case can be: given that I’m looking at a persisted report and I know its reference, when was it created? What events lead to its persistence?

Processing the struct

The processing step is where most of our business logic resides. It’s intentionally left vague as its implementation may change dramatically depending on the intent expressed by the struct name. For these purposes, we’ll once again define a protocol to express this variability, Processable.

defprotocol Processable do

def process(item)

end

To get this to work, we need to do three things:

- import the protocol where the pipeline is defined:

import Processable - define its implementation for

V1.Reports.Create - define

V1.Reports.Created, which we’ll return as expression of the successful processing

The V1.Reports.Created struct can look like the following

defmodule V1.Reports.Created do

defstruct request_id: nil, record: nil

end

As we can see, it exposes the same request_id attribute we saw before and a record attribute, which will be populate with the struct coming from our database driver. We can now implement the Processable protocol:

defimpl Processable, for: V1.Reports.Create do

def process(create_struct) do

{:ok, new_record} = DB.Repo.create(create_struct.data)

%V1.Reports.Created{request_id: create_struct.request_id, record: new_record}

end

end

Note that DB.Repo.create is just an example, the database api will change depending on the persistence layer used.

One may wonder why we bother wrapping the persisted record in a struct instead of just returning the record itself. The reason is that along with the persisted data, we need to pass two extra pieces of information: the request_id, which effectively is metadata about the request and not part of the record itself, and the idea that this record has just been created. V1.Reports.Created expresses both with clarity to the rest of the system, particularly to the subsequent steps in the pipeline.

Logging (part 2)

Logging a report creation requires repeating the pattern we used before, i.e. implementing the String.Chars protocol for V1.Reports.Created.

defimpl String.Chars, for: V1.Reports.Created do

def to_string(created_struct) do

"type=create status=success request_id=#{created_struct.request_id} reference={created_struct.record.reference} id=#{created_struct.record.id}"

end

end

We still key on the same type and indicate success as status, as we want to confirm that processing has been successful. For ease of search, we also log the same reference and the database id. This assumes that both are present in the record that has been persisted by the database. Note that as we define the default value for V1.Reports.Created.record as nil, this implementation assumes a fully populated struct.

Acknowledging the original message

At this point, we can safely acknowledge the message to the client that originally queued it. In RabbitMQ, for example, this means that the message can be safely removed from the queue.

Depending on the setup, this step may not be necessary.

Notifications

The last step in our pipeline is notifying another broker that processing has completed.

A notification message is defined by two attributes:

- a list of topics

- a payload

In code:

defmodule Message do

defstruct request_id: nil, topics: [], data: %{}

end

Consequently, we can expose our pubsub layer via a PubSub.publish/1 function which will happily accept Message structs.

Lastly, we can create a Notification protocol that will define how to go from a given struct to a Message.

defimpl Notification, for: V1.Reports.Created do

def process(created_struct) do

%Message{

request_id: created_struct.request_id,

topics: ["v1.reports"],

data: Map.from_struct(created_struct.record)

}

end

end

The list of topics can be extracted if needed.

Finally, let’s go back to the notify/1 function used in the pipeline:

def notify(item) do

Notification.process(item)

|> PubSub.publish

end

The last step, logging the notification, is identical for all Message structs:

defimpl String.Chars, for: V1.Reports.Created do

def to_string(message_struct) do

"type=publish request_id=#{message_struct.request_id} topics=#{format_topics(message_struct.topics)}"

end

defp format_topics(topics) do

Enum.join(topics, ",")

end

end

Another option is to log one line per topic, but for simplicity reasons we’ll skip that.

Process layout

So far we’ve treated this pipeline as a single-threaded flow, but as we outlined before this should not be the case.

A common scenario is to have:

- a consumers pool, whose job is picking up a message from the queue and eventually acknowledging its successful handling;

- a worker pool, hidden behind

process/1: the processing operation can assume a valid, well-formed struct and the resulting code will be easier to maintain; - a notifiers pool, this time hidden behind

notify/1. By using a pool we can control the pressure put on the external broker, especially because a single job can trigger many different notifications.

All of these techniques can leverage existing libraries in the BEAM ecosystem, so we won’t cover them here.

Error handling

To improve traceability of our pipeline, we want to be able to clearly log failures along the way, knowing exactly which step failed. It’s theoretically possible to infer this from a stack-trace, but it gets unwieldy pretty quickly.

Elixir will introduce a with operator to model a computation dependent on one or more preconditions (see the relevant issue here). For the time being, we can use some macros inspired by the ideas behind Railway oriented programming (see the Elixir specific blog post here and the theory behind it here).

The core of it is that every step of our pipeline will either return {:ok, result} or {:error, reason}, which will allows us either to proceed to the following step or shortcut out of the pipeline and return an error. In other languages, this idea is formalized at the core level as a monad (e.g. Haskell, where it’s defined as a Either type).

Let’s revise the main flow accordingly:

{:ok, message}

>>> identify

>>> populate(message)

>>> log

>>> process

>>> log

>>> acknowledge(client)

>>> notify

>>> log

Except for the final step, where we log the result and pattern match on either a success or an error tuple, we can replace every |> with >>> and tweak our implementations accordingly.

For example, let’s update identify/1:

def identify(payload) do

case payload.meta do

%{"version" => 1, "topic" => "reports", "type" => "create"} -> {:ok, V1.Reports.Create}

_other -> {:error, :unsupported_payload}

end

end

We wrapped the positive result in a tuple, a minimal change with a great benefit.

We won’t update all other methods in the article, as it’s mostly an exercise in copy in paste. As a last consideration, we need to decide if it’s worth capturing the end result of the flow:

def capture_result({:ok, _result}), do: :ok

def capture_result({:error, reason}) do

# send to an exception app, queue an email, queue an error

end

The implementation here can change a lot, but generally it revolves around the question: “What errors do I want to know about?”. We could potentially ignore some errors and track only others, depending on their importance.

Conclusions

In this post we’ve run through a possible approach for the implementation of an event-driven data-processing pipeline in Elixir. The core ideas behind this implementation are:

- define clear boundaries between each step by creating versioned structs

- implement each step as a protocol, so that every versioned struct has a dedicated implementation

- assign steps to different processes, so that they can be scaled independently depending on the needed capacity

- abstract the steps (if needed) behind a clear and composable api, so that there’s only one place in the codebase where the entire pipeline is defined.

- log and trace along the way, always keeping a

request_idparameter at hand to connect all steps together

By following this approach, the benefits are:

- steps isolation, which leads to ease of unit-testing: everything can expressed as “Given struct A, I want to return struct B”

- great traceability

- composability, so that adding a new step is a matter of repeating a pattern

- useful abstraction: each step can be refactored or changed in complete isolation

- ease of scaling, as all the steps run in independent processes

- ability to grow in size but not in complexity: every time a new event is added, it’s sufficient to add the related protocol implementations