This post originally appeared on New Bamboo’s blog.

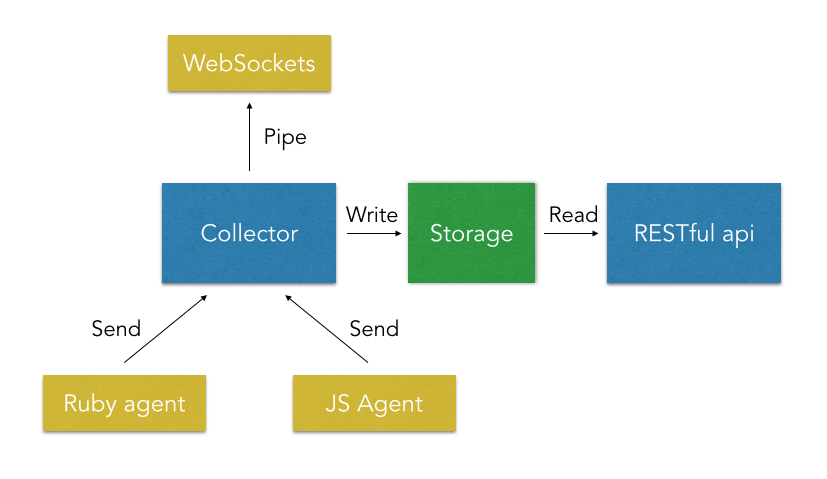

During the last New Bamboo hack day I decided to work on a proof of concept for an analytics service, with the goal of being able to instrument any of our running applications (both server side and client side) and expose the data with a restful api and a web sockets interface (for eventual dashboards, etc.).

After a few days of initial research and preparation, I decided to focus on the storage and RESTful api. I had two questions guiding this prototype.

- How can I store and query reasonably large volumes of data, partly structured and partly unstructured, with a focus on time?

- How can I quickly build a performant RESTful api with minimal amount of code?

What we’re collecting

The sample data I’ve decided to use simulates client side analytics, i.e. recording a page view in a browser.

If we take a low-traffic website and assume 5 page views a minute (a very low estimate), we quickly get to high numbers, i.e. 648k page views in 3 months.

I’ve set this as a baseline data size to work with, in order to identify as early as I could any performance bottleneck that could arise with more significant data volumes.

In terms of requirements, at any point in time the api needs to be able to:

- Access a single page view in the course of the last month

- Aggregate and count page views by day in the last month

- Aggregate and count page views by week in the last 3 months

- Aggregate and count page views by month in the last year

- Slice these measures by a set of pre-made filters (e.g. browser or domain specific ones like an hypothetical

account)

A sample page view record can look like this:

{

"uuid": "0cf61611-fe2e-4b75-a64d-d2b9e61b37ea",

"url": "http: //www.claudio-ortolina.org",

"meta": {

"browser": "chrome",

"account": "new-bamboo"

},

"created_at": "2015-03-20T23:14:00Z"

}

Keys inside the meta attribute may or may not be present (this simulates the usage by different clients, platforms, etc.).

Storage

When thinking about the data, we can summarise a few requirements about the storage:

- Slice and group by period (day, week, month)

- Query across optional dimensions (not all pages would have a browser)

- Aggregation and window-based calculations

The goal was to move as much as I could any data computation to the database, so that my api application layer could do the bare minimum to present the data.

My initial hunch was that Postgresql would have been a great candidate, especially due to its recent support for JSON data formats, so I started with that.

DB schema

We can model a page view as follows:

┌────────────┬──────────────────────────┬───────────────┐

│ Column │ Type │ Modifiers │

├────────────┼──────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ uuid │ uuid │ not null │

│ url │ text │ │

│ meta │ jsonb │ │

│ created_at │ timestamp with time zone │ default now() │

└────────────┴──────────────────────────┴───────────────┘

Starting with Postgres 9.4, we can use JSONB (where B stands for binary) to store json data. This allows use to use Generalized Inverted Indexes (GIN) to index keys in the JSON structure for a much faster lookup.

If we wanted to index the browser attribute we could do:

CREATE index idx_page_views_meta|_browser on page_views USING GIN((meta -> 'browser'));

A subsequent query that uses that index can look like:

SELECT count(*)

FROM page_views

WHERE meta -> 'browser' ? 'firefox';

The -> operator searches for the browser key in the meta object, while the ? operator tests that a document exists where the value is firefox.

More information on JSONB and related operations are available in the changelog and in this blog post by Rob Conery.

Regarding grouping by a time range, we can extract the relevant part of the created_at timestamp and use it to group page views. For example, to group by week over the last month we can do:

SELECT extract(week FROM created_at) AS week,

count(uuid) as page_views_count

FROM page_views

WHERE DATE(TIMEZONE('UTC'::text, created_at)) > date_trunc('week'::text, (now() - '1 mon'::interval))

GROUP BY week

For a more efficient execution, we can add an index on created_at:

CREATE INDEX idx_page_views_created_at ON page_views(DATE(created_at AT TIME ZONE 'UTC'));

The only thing to keep in mind is that we explicitly set an index on the UTC representation of the datetime and cast it accordingly in the query.

So how about performance?

With the specified dataset size (the fake data I’ve created adds up to ~700k page views over the course of 3 months), grouping by day takes on my machine between 400ms and 600ms despite basic optimizations. There are different strategies to fix this, but I’ve opted for a very simple approach: materialized views.

While a standard view is transient and computes its data from its source table(s), a materialized view data is independent from its source. Once created, its data is persisted. It can be refreshed any time.

We can create a materialized view with the aggregation we used above and have a scheduled job that refreshes it every hour or so. This would guarantee a good balance between performance and freshness of the data.

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW weekly_page_views AS

SELECT extract(week FROM created_at) AS week,

count(uuid) as page_views_count

FROM page_views

WHERE DATE(TIMEZONE('UTC'::text, created_at)) > date_trunc('week'::text, (now() - '1 mon'::interval))

GROUP BY week

Refreshing is just a matter of:

REFRESH MATERIALIZED VIEW weekly_page_views;

We don’t need to as the table size is pretty small, but we could potentially add some indexes on this view as well.

By using this technique, the sql execution time gets back in the order of a few milliseconds.

The api layer

Once again, let’s think about requirements for the api stack:

- efficient at crunching numbers

- optimised to build an api

- easy to integrate with custom sql

This seems a good use case for Liberator, an api framework for Clojure, and Yesql, a library that generates Clojure functions from sql code.

Liberator follows a conceptually simple approach: every api endpoint can be implemented by following the decision tree of the HTTP specification (RFC-2616), as also visually outlined in the documentation. This means that I can think of all my endpoints as state machines.

As an example, let’s consider the api request for POST /page_views, used to create a new page view record.

I can express this idea as a resource which can be mounted at a specific url.

(defresource post-pages []

:available-media-types ["application/json"]

:allowed-methods [:post]

:malformed? (fn [ctx] (is-malformed-json ctx))

:post! (fn [ctx]

(create-page (extract-params-from ctx))))

This resource will only allow POST (responding with 501 (unknown method) to any other method). If requested with invalid JSON, it will respond with 400 (malformed).

In case of a well formed request, it will proceed to post!, where we extract the page view parameters from the request body and create a page in the database.

It’s a very elegant approach that combines clarity with simplicity as it stands on the structure provided by the HTTP spec. This way I don’t have to remember to check for malformed content, I can just simply implement the callback.

As for Yesql, I can just write an .sql file with comments in a specific notation:

-- name: all-by-url

-- Finds all page-views filtered by url

SELECT *

FROM page_views

WHERE (url = :url)

LIMIT :limit;

The first comment line defines the function name, the second the help description. Placeholders like :url and :limit will define the arguments accepted by the function itself.

I can have a very short Clojure namespace that imports this file and generate these functions through a macro:

(ns mergen.page-view

(:require [yesql.core :refer [defqueries]]

[mergen.db :as db]))

(defqueries "mergen/queries/page-view.sql"

{:connection db/db-spec})

I can use them by calling:

(page-view/all-by-url {:url "http://google.com" :limit 100})

This query will return a Clojure list with values casted to Clojure types by the underlying JDBC driver. It really just works.

Being the data a data structure, it can be efficiently manipulated using Clojure’s rich standard library, so the result code is particularly succinct.

(defn all-pages-by-week []

(let [raw-data (page-view/all-grouped-by-week)

page-views-data (map serialize-week-count raw-data)]

(generate-string {:page-views page-views-data

:meta { :count (count raw-data)

:total (reduce + (map :page_views_count raw-data))}})))

This function gets all pages by week, serializes them one by one into a more idiomatic structure for JSON output, adds a meta object that exposes a count and a total, finally converting the whole data in JSON.

Conclusion

The final result of this initial prototype shows that there’s a lot of potential in this approach.

Postgres is excellent at storing and slicing data in the format we need and some basic optimisations can take us a long way even when data grows to potentially millions of rows (this just means that materialized views take longer to be generated).

Clojure and the libraries used allowed me to expose Postgres data with a minimal translation effort (it’s just sql) and very little code.

Next time, I plan to explore the other side of the diagram and focus on the data collection and real time processing, which I think it’s gonna be a perfect fit for Elixir.